What is Uveitis?

Uveitis Virtual Education Session

Learning Experience:

Learning Experience:

In this recorded session, you’ll hear more about uveitis (eye inflammation) associated with JIA from Dr. Alan Rosenberg, Pediatric Rheumatologist. You’ll learn where the inflammation occurs, what the risks of the inflammation and treatments are, and get a glimpse into the latest uveitis research. You’ll also hear from a former patient of Dr. Rosenberg’s, Becki Zerr, about their firsthand experience with uveitis and advice to parents.

After several failed attempts at treating chronic “Pink eye,” Cory was finally diagnosed with Uveitis. Hear what it’s been like to manage his eye inflammation over the last 8 years from elementary to high school.

REMINDER: Regular eye screening exams are critical – even when kids have no symptoms.

Frequently Asked Questions

Questions answered by Pediatric Rheumatologist, Dr. Alan Rosenberg. You can ask questions anytime and get connected to other affected families by joining our safe and secure Online Support Network!

Recently, a group of Canadian pediatric rheumatologists, pediatric ophthalmologists and patients and parents have been working together to develop standardized approaches for monitoring and treating children with uveitis associated with JIA. It was felt important to develop standardized approaches because there is some variability in how children with JIA uveitis are managed. The specific question about when and if cyclogyl should be used was not part of our discussions but I can make some comments in response to this question.

First, I think it would be advisable to ask each of the ophthalmologists your question so you have a clear understanding about the rationale for their respective approaches. However, while I am not an ophthalmologist, I do have some thoughts about why there might be differences in approaches.

Cyclogyl is used to dilate the pupil of the eye – that is to make the pupil bigger and stay bigger for the duration of the exam. The pupil appears enlarged when it is dilated because the iris tissue moves outward (and the pupil appears small when it constricts because the iris moves inward to the centre of the eye). By dilating the eye the doctor will have a much wider window to look through into the eye making the eye examination easier. However, once the pupil is dilated an accurate test for vision cannot be done as the effects of the medication can cause blurring of this vision that may last for up to 24 hrs. Also, when the pupils are dilated with cylogyl it is not possible to accurately assess the movement of the iris; sometimes when the iris becomes inflamed, as it does in uveitis, parts of the iris can get stuck down to the lens behind or the cornea in the front; when this binding of the iris to adjacent tissues occurs, these areas of attachment might be less apparent than when the pupil is constricted (gets smaller). When the pupil is dilated with cyclogyl drops it won’t move to the constricted position so that it is more difficult to assess areas where the iris might be attached to the adjacent structures. So, one approach is for the ophthalmologist to have the vision exam and iris movement assessments done without using the dilating eye drops then add the eyedrops later to enlarge the pupil to make the visualization examination of eye with the slit lamp easier.

While the doctors can diagnose and monitor uveitis and prescribe medical treatments, it is essential for everyone on the care team, which includes parents and the patient, to recognize that, depending on the severity of the uveitis, other facets of the child’s life can be affected. If parents realize that there can be effects on the child’s psychological well-being, interpersonal relationships, recreational activities, and schoolwork effects, parents can help minimize these concerns. Doctors will try to educate the children about their disease, but parents can also play a role in helping the child understand their condition and the importance of the treatments. Generally, we advise parents to ensure their child enjoys as normal a life as possible, is physically active, eats a nutritious diet, and gets sufficient rest. Parents are encouraged to communicate with the child’s teachers to ensure they know that the child has uveitis and can tailor the child’s academic experience as required. Parents should also help other children in the family understand the affected child’s condition.

This is an excellent question and one which has been addressed by the committees in Canada and the United States which are developing standardized guidelines for treatment. The answer about the duration of Pred Forte treatment, which is steroid drop treatment, depends somewhat on the severity of the uveitis, the dose of the Pred Forte, and consideration of what other medications the child is taking. A very low dose of Pred Forte – that is, 1-2 drops per day, has been reported to be associated with negligible adverse effects. However, the risk of adverse effects such as cataracts increases with increasing dose. Children receiving more than 3 drops per day for an extended period of time are at greater risk for developing cataracts and children receiving less than 3 drops per day are reported to be 87% less likely than those receiving greater that 3 drops per day to develop cataracts. However, uncontrolled uveitis can also lead to cataracts. So, it is always a balance between good control of the uveitis and the risk of the medications. However, now that we have much better treatments for uveitis in JIA it is more common to be able to use only low doses of steroid drops in combinations with the other therapies.

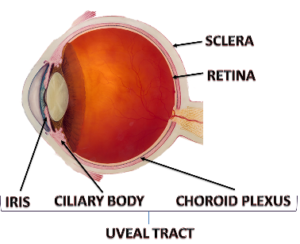

The uveal tract, which is the middle layer of the eye, is that part of the eye that becomes inflamed in uveitis. As shown in the figure the uveal tract extends from the very back of the eye to the very front, ending as the iris (the colored part of the eye surrounding the pupil). In uveitis associated with juvenile arthritis the inflammation of the uveal tract is usually restricted to just the front part of the eye (involving the iris and ciliary body, as shown on the figure). When the entire uveal tract is involved, from the very back of the eye to the very front, it is referred to as pan uveitis. \

While pan uveitis can occur in children with arthritis it is much less common that the uveitis that is restricted just to the front part of the eye (the iris and ciliary body involvement only, which is referred to as anterior uveitis). In addition to occurring in association with juvenile arthritis and other autoimmune diseases, pan uveitis can occur in association with certain infections, and eye injury or surgery, as examples. The inflammatory process involved with pan uveitis and anterior uveitis seems to be similar but further research is required to better explain why some children have anterior uveitis and others pan uveitis.

The course and outcomes of uveitis, including uveitis associated with juvenile arthritis, are variable; some children will have ongoing lingering disease activity and others can go into long-term control (remission). At the present time we can make decisions about treatments based on experiences from large groups of patients with similar conditions. However, the conclusions we make about the diseases and the treatments from studying the group as a whole do not always precisely apply to individual patients within the group, there is considerable variability in how individual patients will respond to treatment.

Now, with new knowledge and technologies, we are beginning to aim for personalized approaches to therapy so that we can select therapies based on the individual’s genetic, lifestyle and environmental factors. We think this personalized approach will result in more uniform and effective responses to therapy. In general, older data suggests that about 1/3 of patients with uveitis associated with juvenile arthritis will have mild or no active disease long term, 1/3 may continue to have mild to moderate disease, and 1/3 will have substantial long term visual impairment. However, more recently, with earlier diagnosis, more rigorous follow up and monitoring of patients, and dramatically improved treatments, we anticipate the long-term outcomes will greatly improve.

We don’t have enough information to answer this question precisely but it is almost certainly true that with early diagnosis, careful monitoring and use of new medications the possibility of permanent remission increases. I wouldn’t say children can “outgrow” uveitis exactly but with proper treatment the abnormal process that gives rise to the uveitis could be stopped with therapy. We hope permanent remission of uveitis can occur with early treatment and new treatments.

The course and outcomes of uveitis, including uveitis associated with juvenile arthritis, are variable; some children will have ongoing lingering disease activity and others can go into long-term control (remission). Now, with new knowledge and technologies, we are beginning to aim for personalized approaches to therapy so that we can select therapies based on the individual’s genetic, lifestyle and environmental factors. We think this personalized approach will result in more uniform and effective responses to therapy. In general, older data suggests that about 1/3 of patients with uveitis associated with juvenile arthritis will have mild or no active disease long term, 1/3 may continue to have mild to moderate disease, and 1/3 will have substantial long term visual impairment. However, with earlier diagnosis, more rigorous follow up and monitoring of patients, and dramatically improved treatments, we now anticipate that long-term outcomes will greatly improve.

At the present time we can make decisions about treatments based on experiences from large groups of patients with similar conditions. However, the conclusions we make about the diseases and the treatments from studying the group as a whole do not always precisely apply to individual patients within the group; there is considerable variable in how individual patients will respond to treatment. Now, with new knowledge and technologies, we are beginning to aim for personalized approaches to therapy so that we can select therapies based on the individual’s genetic, lifestyle and environmental factors. We think this personalized approach will result in more uniform and effective responses to therapy. With earlier diagnosis, more rigorous follow up and monitoring of patients, and dramatically improved treatments, we anticipate the long-term outcomes of uveitis will greatly improve.

The new treatments that are available to treat uveitis (and arthritis) have transformed care and outcomes. The new treatments are referred to as biologic drugs because they are designed to target the precise molecules that participate in inflammation. Currently, these biologic drugs target molecules in the body that usually participate in inflammation. However, with more research we hope to be able to identify exactly what molecule or molecules participate in inflammation in the individual patient so that the exact correct choice of the biologic drug can be selected for that patient. Also, with more research we hope to be able to know better when the biologic drug should be started and when the medication can be safely stopped without causing the disease to recur. Of course, we are continuing to investigate what factors might be involved in causing uveitis to occur in the first place so that we can consider ways to prevent uveitis from occurring. New biologic treatments, that target an increasing number of proteins that contribute to inflammation, are being developed at a very rapid pace so new drugs are becoming available on a regular basis.

Assessing the microbiome is a complex, laboratory-based process. Doctors cannot effectively assess the microbiome by asking the patient questions or by findings on a physical examination. To effectively assess the intestinal microbiome a stool sample needs to be collected and processed in the laboratory so that the molecular and genetic characteristics of the bacteria in the sample can be determined. To determine which bacteria are in the sample from the intestine the laboratory will determine the genetic characteristics of each of the bacteria. We are also beginning a study that will be investigating the oral microbiome by collecting saliva samples and samples from around the teeth and gums as we suspect that the oral microbiome might have some influence on juvenile arthritis. We don’t know if the oral microbiome might be associated with uveitis but our study should help improve understanding of this possible connection.

This is a fascinating question and one for which there is accumulating but still minimal information. There is some evidence that maternal use of antibiotics either before or during pregnancy or at the time of labor might result in changes in the microbiome of the child born to that mother. There have been no studies done specifically to investigate if maternal antibiotic use during pregnancy might affect the risk of the child developing JIA or uveitis. We are currently doing a research study to investigate how inflammation during pregnancy might influence future disease in the offspring. One facet of this study is to look at antibiotic use during pregnancy and the risk of the offspring having certain diseases later in life. We are also just about to begin a research project to study if the microbiome in the mouth influences the occurrence and course of JIA and if there is any connection with the oral microbiome and uveitis.

Recently, a group of Canadian pediatric rheumatologists, pediatric ophthalmologists and patients and parents have been working together to develop standardized approaches for monitoring and treating children with uveitis associated with JIA . It was felt important to develop standardized approaches because there is some variability in how children with JIA uveitis are managed. In both the Canadian and similar United States guidelines that are being developed in children with JIA and uveitis who are starting treatment other than eye drops for uveitis, using injection of methotrexate is recommended over oral methotrexate.

In general, evidence suggests that injection of methotrexate works better for both arthritis and uveitis. Thus, if the child was on oral methotrexate before the injection and the switch was made to achieve better control of the JIA and/or uveitis, then switching back to oral methotrexate might or might not result in a flare. The decision the doctors might have to consider is not when to switch to back to oral methotrexate but when to try to discontinue methotrexate entirely. Deciding when to stop methotrexate would depend on how severe the uveitis was, how difficult it was to control, and if the child is on other medications. In the guidelines that are being developed, in children with uveitis that is well controlled on a medication such as methotrexate with or without other therapy, it is recommend that there be at least 2 years of well-controlled disease before tapering and then discontinuing the therapy.

So, in a child with at least 2 years of inactive disease one might soon consider beginning a slow taper of current medications rather than switching to oral methotrexate. But again, this depends a lot on the individual patient’s characteristics and treatments now and in the past. Studies are underway to gather evidence that will help guide when medications can be safely stopped without risking flare ups.

Long term effects of uveitis can be minimized by prompt diagnosis, consistent monitoring, and appropriate use of medications. Some of the main effects that can occur and which we try to avoid with therapy include the following:

- Decrease in vision: When there is inflammation in the eye, such as occurs with uveitis, there can be increased amounts of protein and inflammatory cells in the eye that interfere with light passing through the eye. As a result, the ability to see clearly can be reduced.

- Cataracts: A cataract is a painless clouding of the usually crystal clear lens of the eye. The lens sits behind the pupil of the eye as shown in the figure. Cataracts block light, making it difficult to see clearly.

- Synechiae: Synechiae can occur as a result of uveitis. Synechiae are adhesions of the iris so the lens becomes stuck to either the lens below or the cornea in front (the cornea is a clear membrane window that lies in front of the pupil). When such adhesions occur, the iris will not move as freely. Normally the iris will dilate (spread out) so the pupil enlarges when the environment is darker (allowing more light to enter the eye) and in bright light will constrict (come together) so the public gets smaller limiting the amount of light entering the eye. When synechiae are present the movement of the iris is impeded and this can result in difficulty in adapting to light changes in the environment.

- Band Keratophathy: Band keratopathy is a line or band that appears across the center of the cornea. The band forms when calcium deposits collect in this area. Band keratopathy can reduce vision and sometimes causes eye irritation or redness.

- Increased eye pressure (glaucoma): Glaucoma can occur in some children with uveitis because the normal flow of fluids in the eye might be limited because of the inflamed tissues. Steroid medications can sometimes increase the eye pressure.

This is a very interesting and important question. Yes, uveitis can result from injury to the eye such as a blunt force to the eye or a foreign body in the eye. This usually results in iritis, which is inflammation of the colored part of the eye that surrounds the pupil. The iris is also one part of the eye that is typically inflamed in uveitis associated with JIA. There is also information from laboratory experiments suggesting that trauma in a joint can result in changes in certain molecules in the cornea of the eye (a part of the eye which is not primarily involved in uveitis associated with JIA). More research needs to be done to understand how trauma to the eye or in the joint might be associated with chronic uveitis as is seen in association with JIA.

There are seven different types of Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis.. It is uncommon for most forms of JIA to occur in siblings; children who present with the type of JIA referred to as ERA (Enthesitis Related Arthritis ; enthesitis refers to inflammation where ligaments and tendons insert onto bone), which tends to occur in older children and is more common in boy, are more likely than other JIA subtypes be found in siblings. In children with the type of JIA referred to as oligoarticular JIA (children with fewer than 5 joints involved; the word “oligo” comes from the Greek word meaning “few”) are the most likely to have uveitis that is chronic and generally not associated with symptoms such as redness of the eyes or eye pain . Oligoarticular JIA occurs uncommonly in siblings but it can occur. The occurrence of oligoarticular JIA with associated uveitis is even more rare but again it can occur. The type of uveitis associated with ERA tends to be associated with symptoms and intermittent brief courses; this type of arthritis is thought to be somewhat more likely to occur in siblings with the ERA type of JIA but the occurrence is still uncommon. The fact that JIA and JIA with uveitis can occur in siblings, although rarely, suggest the possibility of a genetic influence on the occurrence of the disease or an environmental exposure or, perhaps more likely, an interaction of genes with the environment. More research is required to answer this important question. Because JIA and JIA with uveitis occur rarely in siblings, international research collaboration, such as that which is being led by Canadian pediatric rheumatologists and ophthalmologists, will be important to help answer this question more thoroughly.

At present, we can decide treatments based on experiences from large groups of patients with similar conditions. However, the conclusions we make about the diseases and the treatments from studying the group as a whole do not always precisely apply to individual patients within the group; there is considerable variability in how individual patients will respond to treatment. Now, with new knowledge and technologies, we are beginning to aim for personalized approaches to therapy so that we can select therapies based on the individual’s genetic, lifestyle, and environmental factors. We think this personalized approach will result in more uniform and effective responses to therapy. In general, older data suggests that about 1/3 of patients with uveitis associated with juvenile arthritis will have mild or no active disease long term, 1/3 may continue to have mild to moderate disease, and 1/3 will have substantial long term visual impairment. However, more recently, earlier diagnosis, more rigorous follow-up and monitoring of patients, and dramatically improved treatments, makes us believe that the long term outcomes will significantly improve.

The new treatments that are available to treat uveitis (and arthritis) have transformed care and outcomes. The new treatments are referred to as biologic drugs because they are designed to target the precise molecules that participate in inflammation. At the present time these biologic drugs target molecules in the body that usually participate in inflammation. However, with more research we hope to be able to identify exactly what molecule or molecules participate in inflammation in the individual patient so that the exact correct choice of the biologic drug can be selected for that patient. Also, with more research we hope to be able to know better when the biologic drug should be started and when the medication can be safely stopped without causing the disease to recur. Of course, we are continuing to investigate what factors might be involved in causing uveitis to occur in the first place so that we can consider ways to prevent uveitis from occurring.

Research is crucial to advancing knowledge about the causes, mechanisms, and treatment for uveitis. In all our research now, including our studies relating to uveitis and childhood arthritis, we ensure that parents and patients are represented on our research teams. We feel it is important for patients and parents to contribute their ideas and perspectives as we develop research projects, interpret results, and disseminate our research results to end-users such as health care providers, administrators, and patients and families. For conditions such as uveitis and childhood arthritis, most of the time, we do not know the cause of the disease, we do not fully understand the mechanisms of the disease, we have treatments that are much improved but still not as predictably effective or as safe as we desire, and we have no insight into cure and prevention. However, there has been astonishing progress in gaining new knowledge. Based on that new knowledge, it is likely that uveitis and childhood arthritis occur because of multiple factors, including, as examples, genetics, environment, and lifestyle.

Parents can help by identifying possible factors that they wonder might influence the diseases’ occurrence and courses. We encourage parents to ask questions, share their thoughts, and participate fully in the process of learning more. Parents should not feel hesitant to ask questions and share their thoughts. It is also important for parents and patients to share their thoughts about the therapies they receive in terms of their effectiveness and side effects. As technologies advance, we can now aim to personalize treatment approaches; that is, rather than selecting therapies for groups of children with similar conditions, we are now beginning to individualize treatment choices for individual children based on their unique genetic, environmental, and lifestyle considerations. Parents and the patients themselves will be crucial in helping to make personalized choices for therapy.

Our Canadian research, looking at over 1,000 children newly diagnosed with JIA, has shown that the most important contributors to probability of uveitis are a positive ANA and being diagnosed at a young age. Uveitis was most commonly seen in children with either oligoarthritis or polyarticular rheumatoid factor negative JIA. We also saw that there was an incidence of new uveitis among these children of 2.8% per year for the 5 years of the study. This means that children with JIA need to continue to be screened for uveitis for at least 5 years after diagnosis.

Children with JIA can develop uveitis at any time, even when their arthritis is not active. For some children with JIA, the arthritis inflammation becomes quiet, but they have continued uveitis requiring treatments. Similarly, arthritis can flare up at unpredictable times as well. The inflammation isn’t ‘switching back and forth’- the inflammation of JIA can involve different areas at different times.This is the reason that it is important for children with arthritis to have eye examinations as recommended by the pediatric rheumatologist and ophthalmologist even when a child appears to be well! In patients with both uveitis and arthritis we always try to select treatments that are effective for both areas of inflammation.

Real Stories from our Community

Seeing Possibilities after Diagnosis: a Uveitis Story

Throughout my life I have been granted many titles; mom, wife, daughter, registered nurse, and writer are just a few. These are the titles that are associated with my name. I could be described [...]

Becki Zerr: No Stranger to JA and Uveitis

Uveitis (inflammation of the eye) is a serious complication occurring in 20% of children with Juvenile Arthritis, a condition that is hard to diagnose without regular eye screening. Treatment of Uveitis can often be [...]

Uveitis: Scarlett’s Story

In Spring of 2018, my 6 year old daughter was complaining of neck pain. It was mistaken as pain from her twice a week swimming lessons. One morning in August that same year she [...]

Additional Resources

- About Kids Health

AboutKidsHealth is a health education website for children, youth and their caregivers from the experts at SickKids Hospital. The website offers a variety of Uveitis and JIA resources for parents and youth.

- Canadian Association of Optometrists

Learn more about anterior uveitis.

- Uveitis.org

More information and resources specific to Uveitis.