New Series: Ask the Expert + FAQ Hub

Questions about juvenile arthritis and childhood rheumatic disease? We’ve got you covered!

We’ve recently launched a new series called Ask the Expert that connects you and your questions directly with a pediatric rheumatologist so that you can get the answers you need and leave feeling reassured.

Our first session, with Dr. Nadia Luca, Pediatric Rheumatologist at Alberta Children’s Hospital and member of the Cassie + Friends Medical Advisory Committee, covered a variety of JIA topics. Check out the recording below!

In addition to our new series, we’ve collected frequently asked questions (FAQs) and answers to help your family navigate your rheumatic disease journey. Whether you’re newly diagnosed, awaiting diagnosis, or just looking to learn more, the information below has been carefully put together by experts across the country.

Have a question you’d like answered? You can email us at info@cassieandfriends.ca.

The natural history of arthritis is that it comes in flares, so it is not uncommon to have a flare-up

after remission, especially if you have stopped treatments. Most patients go back into

remission. Sometimes you need to change or adjust your current treatment regimen. If you

stop a medication and get a flare-up, most patients go back into remission after the previous

medication is restarted.

Biologics used to treat ERA include adalimumab (Humira or biosimilar), etanercept (Enbrel or biosimilar) and infliximab (Remicade or biosimilar). Some patients

with ERA have another associated condition like uveitis or inflammatory bowel disease. In these cases, this would affect which biologic you would select in discussion with your health care team.

At this time, most of the research for peptide-based therapies has been in animal models of rheumatoid arthritis with some promising results. More studies are needed in humans to determine whether these are feasible and effective treatments. Typically novel therapies are developed and tested in adults before they are studied in pediatric patients.

Yes, there are a new class of biologics that are oral, called JAK inhibitors. This includes a medication called tofacitinib (Xeljanz) that has been studied in children with polyarticular JIA. These medications will become more commonly used in a variety of diseases, and hopefully more available to children and teens.

At present, it is not known what factors- symptoms, lab tests, or disease type- put a patient at higher risk of flare off medication. Your doctor is the best to evaluate whether the symptoms you describe are due to active inflammation, or perhaps due to other issues.

We do not know if taking a biologic treatment for a longer period will influence the chance of a long lasting remission of disease. Each patient is very individual, and other factors, such as type of disease and previous flares, likely have influence over chance for disease remission off medications.

In university it can be easy to get overwhelmed with workload and focus solely on your school work rather than your body. There have been times where I took my medication late, or didn’t listen to my body in order to get work done. Although I thought this wasn’t a big deal, it caused negative effects in the long-run. I ended up experiencing flare ups, extra fatigue, and burnout. Thus, I recommend putting your health first, above all else. Make sure you stop on top of your medication schedule, and if something feels off, write it down in your notes (and include the date) so you ensure you’re documenting your health properly and can look at the progress of your symptoms. These notes will come in handy when you speak with your doctor and will help you recognize the result of your medication management. Additionally, if you feel tired and your body needs rest, listen to your body. Universities have accommodation measures in place for this exact reason.

The best piece of advice I can give is to A) coordinate with your doctor and a nearby pharmacy to have access to your medications while studying at university and B) research your university’s accommodation practices prior to starting at the university, or as soon as you can. In my case, I did not inquire about these accommodations because I felt like I didn’t need them. However, halfway through my first semester, I had a flare up and it affected my ability to write. Consequently, I was rushed into obtaining the required documentation from my doctor in order to get the accommodations before a long hand-written exam. However, once this process was completed, the accommodations were great. I received a “fluctuating condition” letter, which I can present to my professors if I need extensions for assignments because of my health. At the University of Ottawa, many accommodation measures are offered, depending on your needs. Some include a personal note-taker, extra time on exams, being able to type instead of hand write answers, getting deadline extensions, etc. These accommodations vary depending on your university, but it is definitely worth researching

Both biologics and biosimilars are created in living cells. Biosimilars are drugs that are highly similar to an originator biologic that has already been approved by for use by regulatory bodies. This means that there cannot be any meaningful differences between the biosimilar and the reference drug with respect to effectiveness and safety. In order to establish biosimilarity, extensive analytical testing confirms matching of structure and function of the drug, followed by limited but targeted clinical trials in a patient population to demonstrate the same efficacy and safety. For approval of a biosimilar, it is not necessary to repeat studies in all the conditions for which the drug is used, as extrapolation is used for the other conditions for which the reference biologic is approved.

The information we have to date on use of biologic treatments in adolescents do not indicate that there should be any concern that these treatments affect puberty or development in any way. As your teen goes into his growth spurt, his doctors may change his doses to account for weight increase.

Gelatin and collagen hydrolysates have been used in pharmaceutical and food products for years, and as such are generally regarded as safe. However the only evidence for potential benefit has been described in adult osteoarthritis, not in pediatric rheumatic conditions. There are also no dosing guidelines for gelatin and collagen hydrolysate supplements in pediatrics. Speak to your Rheumatologist about adding gelatin/collagen hydrolysates as complementary therapy to your child’s current medical regimen, as it may help with pain or discomfort.

It is unknown at this time what role sugar plays in autoimmune or rheumatic conditions. What has been described is an increased risk of developing autoimmune or rheumatic conditions among adults whose diet is rich in simple sugars (not sugar or carbohydrate from grains, fruits, vegetables, pulses). As part of eating well, simple sugars from juices, pop, sweet treats, drinkable dairy products, added into processed foods like high fructose corn syrup should be limited, regardless of rheumatic diagnosis. As well, overweight and obesity is associated with diets rich in simple sugars, and becoming overweight or obese can negatively impact a child’s journey with a rheumatic condition e.g. limit mobility, affect disease activity (studies in adults), increase risk of other comorbid conditions (e.g. fatty liver disease). Risk of becoming overweight or obese in childhood increases with some medications, like Prednisone, so close growth monitoring is important.

Cassie + Friends will post the slides from the nutrition talk, as well are working to create some nutrition focused resources like snack ideas, which will be posted soon. Some ideas to try in the meantime include: nut or seed butter protein bars/balls, egg muffins, lettuce wraps with vegetables, avocado and source of protein in the middle, chia seed pudding, muffin in a mug, yogurt parfaits (try making homemade granola as source of whole grains and nature’s sweets like honey or maple syrup), quesadilla (add veggies and pulses for added nutrients), stir fry or potato latkes nests with veggie and protein in the center, sweet and/or savoury skewers (e.g. cherry tomato + cheese ball + cucumber on a stick OR banana + apple + nut butter holding fruit together on a stick), bean dips with veggies, nut free trail mixes and sushi rolls.

Fasting and/or intermittent fasting is not advised for either treatment of rheumatic conditions or for weight loss in children and adolescents as this dietary approach may compromise growth and development.

There are no dosing guidelines for curcumin in children as adjunctive support in rheumatic conditions. Studies using curcumin in adults are also limiting. Let your Rheumatologist know if you are adding curcumin as supplement/medicine (vs added to foods as a spice or as part of cooking methods where there is no upper limit described). There are also side effects to consider when administering curcumin including GI symptoms like constipation, bloating, flatulence; vertigo and allergic reactions, so more is not better (Natural Medicines NHP database).

There is little evidence that food sensitivities/intolerance are associated with disease activity. So food sensitivities/intolerance may not necessarily help with inflammation or pain in arthritis. However some patients do report reduced pain, better mobility and better sleep (thought to be secondary to reduced pain) when avoiding foods that have been identified as sensitivity/intolerance. If you/your child have identified some food sensitivities/intolerances, then speak with your rheumatology team about eliminating these foods from your diet to monitor any effect on inflammation (labs, imaging) and/or pain. CAUTION: multiple food (especially food group) eliminations (for example gluten, dairy, soy, egg and nightshade free diet) can be associated with severe malnutrition, growth faltering, reduced quality of life – so it is strongly advised to eliminate only 2 or 3 foods at a time and seek RD support to ensure that you/your child’s nutritional needs are not compromised.

IBD is much like other rheumatic conditions, like JIA or SLE. While there is a lot of interest and research in the area of diet and causes of IBD or dietary causes of flares, there is limited evidence at this time that a diet can treat Crohn’s or UC. There is however very good evidence that one type of diet, called exclusive enteral nutrition, is effective at inducing remission in certain types of Crohn’s disease. Exclusive enteral nutrition is prescribed by a gastroenterologist. Eating well for IBD is very much the same as autoimmune inflammatory rheumatic conditions, with focus on whole real foods, limit packaged/processed foods, rich in whole grains, rich in fruits and vegetables, limiting in red meat incorporating more plant based proteins, and limiting simple sugars/treats.

Vitamin and/or mineral supplements beyond what is needed for growth and development (known also as the dietary reference intakes which are based on age and sex) are not needed to boost the immune system in autoimmune conditions. There is little evidence that “more” of a vitamin or mineral, beyond what your teen would get from eating lots of fruits and vegetables, further supports the immune system. Vitamins and minerals are not benign, meaning over-nutrition or over-supplementation can be associated with side effects, so balance is key. Also to note that while red meat is a source of protein it is not needed in the diet. However a balance of protein sources, such as egg, poultry, fish, pulses, nuts, carbohydrate sources such as vegetables, whole grains and fruits, as well as healthy fats like olive oil, avocado are recommended.

Anxiety is very common amongst the general population of children and teens. We also know that some children with hyper-IgD syndrome have significant effects of this auto-inflammatory disorder on the brain during development, resulting in neuro-behavioral issues. Anxiety might be one behavior that results from the difficulty coping with daily routines that are challenging for someone with hyper-IgD syndrome.

There are numerous professionals with expertise in treating selective mutism. Addressing the selective mutism might help your teen and you to feel more confident when she transitions to adult care. In addition, talk to your pediatric rheumatology team, and together you can develop a plan specific for your teen that will take into account their challenges.

I assume you are talking about neuropsychiatric disorder such as ADHD, Tourettes, and neurodevelopmental disorders such as autism. It is important to know that these disorders are common in the general population of children, so we do see children who may have BOTH JIA and a neurodevelopmental disorder. Research has not shown higher rates of ADHD or other neurodevelopmental disorders in children with JIA.

There is some emerging research that is looking at disregulation of the immune system as a potential underlying cause of autism. However, this is an emerging area of research and it is important for more study to be done on this before any conclusions can be drawn.

In some rheumatic diseases, such as systemic lupus or vasculitis, involvement of the brain is well known, although does not affect all patients. Some children with periodic fever disorders may have inflammation affecting the brain as well. Many other rheumatic diseases, such as arthritis, are not known to directly affect the brain with inflammation, as the inflammation of arthritis is local to the joints.

I am not aware of any research that suggests higher rates of ADHD in children with JIA.

This is one of those specific rheumatic diseases where more study is needed regarding the psychological impact of JDM. I am aware of a couple of studies that look at quality of life in youth with juvenile dermatomyositis that show lower quality of life than peers.

There is no current research on CBD products in children or adolescents, either for general health issues or treatment of chronic arthritis or mental health issues. There are risks associated with the use of these products and therefore they are not recommended for children at this time.

SRIs (serotonin-reuptake inhibitors) have been shown to offer benefit to some individuals for anxiety and depression. Medications might be something to consider for those with moderate to severe symptoms and when there is substantial functional impact from the symptoms. As for children/youth with rheumatic disease, you will need to talk with your prescribing doctor and pharmacist to determine if there are any contraindications to using an SSRI with any medications your child/teen might be taking.

Keep an eye out for those common presenting behaviours that often present with children/teens who are experiencing mood challenges. They include the following:

- Irritability/anger, moody

- Persistent sadness or feelings hopelessness, worthlessness or having excessive guilt

- Not enjoying things they used to enjoy

- Behavioural concerns (increase in defiance or tantrums, clingy

- Withdrawn

- Changes in energy level, appetite or sleep

- Trouble concentrating or making decisions

- Suicidal ideation/self harm

- increase in physical complaints

If you are concerned reach out to the medical team or a mental health professional and they can further assess and identify supports that might be helpful.

Yes, there are many things that can be done to reduce anxiety about receiving needles. For some parents, this means coming up with a coping plan- things like using distraction, giving the child a sense of control by offering options (e.g., where the injection goes, look away, using numbing cream, identifying distractions to use). If you find that you need support with this, you can always talk to the team about what supports might be helpful (e.g., psychologists with expertise in this area). They can help your child learn coping strategies, come up with a gradual exposure plan (I talked briefly about this during the Mental Health Webinar above), and work with you on some parenting support strategies that can be helpful. The AnxietyCanada website has some useful strategies for supporting your child who is exhibiting anxiety.

Your question really highlights how challenging it can be to parent a child with a chronic health condition who is struggling both physically and emotionally. Oftentimes, parents worry about saying the wrong thing or not doing it well enough, but what I find is that intent matters and kids/teens remember that. Being able to have conversations about the challenges, to really hear your child and to be able to sit with them during those times when they have challenging emotions or circumstances is so important and can oftentimes lead to productive conversations about what might be helpful.

Rates of depression tend to rise as children enter adolescence, especially among females. Rates of depression in preschoolers is approximately 1 percent, 2 percent of school-aged children, and 5 to 8 percent of adolescents

Irish sea moss or seaweed is rich in antioxidants and can be a part of healthy eating. Seaweed has been eaten by many cultures for centuries. However there is no evidence about the safety or efficacy of seaweed in controlling inflammation or treating rheumatic conditions in children. This includes safe doses of seaweed if packaged as supplements. Speak to your healthcare team about seaweed supplements as part of your child’s health.

There is little evidence that shows that vitamin(s) or supplements can control inflammation or treat rheumatic conditions in children. Studies looking into antioxidants like vitamins A, C and E supplements did not necessarily treat disease, but these nutrients are important for growth and development. Vitamin D is necessary if levels are low and taking a vitamin D supplement daily to meet optimal status is not harmful. Calcium supplements are needed if the diet is low in calcium. Adding omega-3 supplements can be a part of healthy eating but are not necessary if the diet contains foods rich in these fats like olive oil. Speak to your healthcare team about vitamins or supplements as part of your child’s health.

Children do not need to be put on low sodium diets, however limiting sodium is advised as part of healthy eating. Sodium, also known as salt, is naturally found in many foods. Limit foods preserved with sodium and avoid adding table salt to meals and snacks. Use fresh or dried herbs and spices to add flavour to foods. Cutting down on salt can also lower your risk for high blood pressure and may reduce calcium loss from bones, which is associated with poor bone density (osteoporosis) and fracture risk. Be very mindful of sodium intake if you are taking corticosteroids, like prednisone, often used to treat rheumatic conditions. Corticosteroids have side effects like water retention and high blood pressure, which can worsen with too much sodium in the diet.

Turmeric is a flowering plant from the ginger family. Curcumin is bright yellow and comes from turmeric roots used in cooking. Both turmeric and curcumin have anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties, which can be a part of healthy eating. However there is little specific evidenced-based research that shows that turmeric or curcumin are able to control inflammation or rheumatic conditions. There are also no studies that have looked at the safety of taking large amounts of turmeric, as a supplement, especially in children with rheumatic conditions. Speak to your healthcare team for information about turmeric or curcumin as complementary or alternative therapy for your child’s health.

The World Health Organization says that children need at least 1 gram of protein per kilogram body weight every day to meet protein needs for growth and development. This is why a source of protein is recommended for every meal and ideally in every snack. Try plant based proteins more often, including nuts and nut butters, seeds, pulses (peas, chickpeas, beans and lentils) and whole grains like quinoa. Other tasty proteins include eggs, yogurt, cheese, or lean meats like poultry and fish.

There is little evidence that shows that vegetarian or vegan diets are better at controlling inflammation or treating childhood rheumatic conditions. However a theme that aligns with a healthy diet and is encouraged is eating vegetables and whole grains more often. Vegetarian or vegan diets may also be important for cultural or religious beliefs, and these are always respected by your health care team.

With respect to nutrition, vegan diets may limit certain nutrients, like protein, when compared to vegetarian diets, which may affect growth and development. Research has also shown that blood levels of vitamin B12, vitamin D, calcium and essential fatty acids are lower in people following vegetarian, and even lower in those following vegan diets, when compared to omnivores (people that eat both plants and animals). Speak to your healthcare team for more information about vegetarianism or veganism and your child’s health.

There is little evidence that shows that dairy causes or treats inflammation. However dairy or milk-based products contain many nutrients and active compounds, including calcium, vitamin D, healthy fats and proteins. While Health Canada no longer focuses on dairy as a food group, it can still be part of tasty, healthy eating. Just be mindful of portion size, calories, sugar content and sodium when choosing dairy products for healthy eating. Try plain yogurt with fruits instead of yogurt-based drinks, or a smoothie with fruits and plain yogurt for a source of gut healthy probiotics instead of juice. Or try a bite of creamy aged cheese instead of a processed cheese spread in a sandwich.

There is little evidence that shows that eliminating gluten is effective for treating rheumatic conditions in children. Gluten is protein naturally found in the grains including wheat, barley, rye and triticale. It is also found in many packaged, preserved foods as a filler. More research is needed to better understand if gluten has any role in rheumatic conditions.

There are also nutrition considerations with a gluten free diet. Gluten-free foods, compared to gluten containing equivalents, are often higher in calories, sugar and fats, but lower in fiber. So a gluten-free diet full of gluten-free packaged products is not necessarily healthy. The gluten-free diet can also affect your ability to meet nutrient needs for growth and development. Speak to your healthcare team for more information about gluten and your child’s health.

There are no specific foods that should be eliminated from the diet of children with rheumatic conditions in order to treat the disease. There are foods however that should be limited.

Limit foods rich in simple sugars such as sugary cereals, sugary yogurts, treats such as donuts or cereal bars, and fruit juices. Foods containing high amounts of simple sugars (e.g. high fructose corn syrup, syrup solids and sucrose) often have little nutritional benefit and may be associated with cravings soon after eating. Refined foods such as white breads, pasta, and cereals are low in fibre. Choose whole grain or whole wheat breads, bagels, wraps and cereals, or pastas made from buckwheat or lentils, and wild rice for added fibre.

Limit sodium. Sodium, also known as salt, is naturally found in many foods. Limit foods preserved with sodium and try not to add table salt to meals and snacks. Use fresh or dried herbs and spices to add flavour to foods. Cutting down on salt can also lower your risk for high blood pressure and may reduce calcium loss from bones, which is associated with poor bone density (osteoporosis) and fracture risk. Be very mindful of sodium intake if you are taking corticosteroids, like prednisone, often used to treat rheumatic conditions. Corticosteroids have side effects like water retention and high blood pressure, which can worsen with too much sodium in the diet.

Limit saturated and trans fats. Saturated fats are fats that stay solid at room temperature. Saturated fats are found in foods such as meats and butter. Trans fat are processed fats. Hydrogen is used to change vegetable oils into a semi-solid fat. You’ll find trans fats in commercial baked goods, fried and deep-fried foods and margarine.

There are no specific foods that have been shown to treat rheumatic conditions in children. There is also no evidence that avoiding foods labeled as “pro-inflammatory” can treat rheumatic conditions. We think of “treatment” as something (e.g. medication, physiotherapy) that decreases the underlying inflammation and damage associated with the condition. We do know that nutrition may make a difference to how one feels, for example decreasing pain, and also benefits overall health, growth and development.

Healthy eating is a balanced diet rich in real whole foods such vegetables, fruits, whole grains and lean animal proteins, like the Mediterranean diet. Healthy eating limits packaged and processed foods that are rich in sodium, preservatives, simple sugars and unhealthy fats.

Healthy eating also means eating regularly. This includes eating three meals per day with snacks in between. Eating regular meals will support your child’s energy levels throughout the day and can help maintain a healthy weight. Eating regularly also means trying not to skip meals. Be sure to start the day with breakfast and remind your child to eat when away from home, like school lunch breaks. Sometimes it helps to package small meals that are easier to eat when school breaks are short.

Adding proteins to meals and snacks is also encouraged. Protein is important for growth and development. Protein can also help your child feel fuller longer. Try plant based proteins more often, such as nuts and nut butters, seeds, pulses (peas, chickpeas, beans and lentils) and whole grains like quinoa. Other tasty proteins include eggs, yogurt, cheese, or lean meats like poultry and fish.

When children are hungry, they may crave snacks that are high in simple carbohydrates such as crackers or toast. Snacks are meant to be small meals and can include whole grains, protein(s) and good fats like nuts and nut butters, hummus or avocado, which can also help satiate hunger. Whole grain sources of carbohydrate include whole wheat, wild rice, quinoa and vegetables. Snack ideas include vegetables with hummus or yogurt with berries and granola or lettuce wrapped turkey with avocado slices or mini fish tacos with salsa and cabbage slaw.

It might be helpful to you to have a conversation with your child’s doctor to better understand how they are using the lab test results, and this might help you feel more comfortable that you don’t need to concentrate only on the numbers, and in understanding how medication decision-making happens.

For most of the medications that are used to treat children with arthritis (naproxen, methotrexate, biologics), medication levels are not tested in blood tests. The lab tests that are done are usually to monitor possible side effects, such as elevated liver function tests; standard practice is to check surveillance labs approximately every 3-4 months In most circumstances, the level of an inflammatory marker on a blood test would not be used as the sole reason for intensifying or decreasing medication. Deciding in changing medication would include knowing your child’s current symptoms and their physical examination.

Recently, a group of Canadian pediatric rheumatologists, pediatric ophthalmologists and patients and parents have been working together to develop standardized approaches for monitoring and treating children with uveitis associated with JIA. It was felt important to develop standardized approaches because there is some variability in how children with JIA uveitis are managed. The specific question about when and if cyclogyl should be used was not part of our discussions but I can make some comments in response to this question.

First, I think it would be advisable to ask each of the ophthalmologists your question so you have a clear understanding about the rationale for their respective approaches. However, while I am not an ophthalmologist, I do have some thoughts about why there might be differences in approaches.

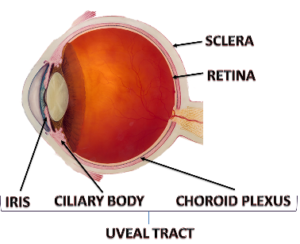

Cyclogyl is used to dilate the pupil of the eye – that is to make the pupil bigger and stay bigger for the duration of the exam. The pupil appears enlarged when it is dilated because the iris tissue moves outward (and the pupil appears small when it constricts because the iris moves inward to the centre of the eye). By dilating the eye the doctor will have a much wider window to look through into the eye making the eye examination easier. However, once the pupil is dilated an accurate test for vision cannot be done as the effects of the medication can cause blurring of this vision that may last for up to 24 hrs. Also, when the pupils are dilated with cylogyl it is not possible to accurately assess the movement of the iris; sometimes when the iris becomes inflamed, as it does in uveitis, parts of the iris can get stuck down to the lens behind or the cornea in the front; when this binding of the iris to adjacent tissues occurs, these areas of attachment might be less apparent than when the pupil is constricted (gets smaller). When the pupil is dilated with cyclogyl drops it won’t move to the constricted position so that it is more difficult to assess areas where the iris might be attached to the adjacent structures. So, one approach is for the ophthalmologist to have the vision exam and iris movement assessments done without using the dilating eye drops then add the eyedrops later to enlarge the pupil to make the visualization examination of eye with the slit lamp easier.

While the doctors can diagnose and monitor uveitis and prescribe medical treatments, it is essential for everyone on the care team, which includes parents and the patient, to recognize that, depending on the severity of the uveitis, other facets of the child’s life can be affected. If parents realize that there can be effects on the child’s psychological well-being, interpersonal relationships, recreational activities, and schoolwork effects, parents can help minimize these concerns. Doctors will try to educate the children about their disease, but parents can also play a role in helping the child understand their condition and the importance of the treatments. Generally, we advise parents to ensure their child enjoys as normal a life as possible, is physically active, eats a nutritious diet, and gets sufficient rest. Parents are encouraged to communicate with the child’s teachers to ensure they know that the child has uveitis and can tailor the child’s academic experience as required. Parents should also help other children in the family understand the affected child’s condition.

This is an excellent question and one which has been addressed by the committees in Canada and the United States which are developing standardized guidelines for treatment. The answer about the duration of Pred Forte treatment, which is steroid drop treatment, depends somewhat on the severity of the uveitis, the dose of the Pred Forte, and consideration of what other medications the child is taking. A very low dose of Pred Forte – that is, 1-2 drops per day, has been reported to be associated with negligible adverse effects. However, the risk of adverse effects such as cataracts increases with increasing dose. Children receiving more than 3 drops per day for an extended period of time are at greater risk for developing cataracts and children receiving less than 3 drops per day are reported to be 87% less likely than those receiving greater that 3 drops per day to develop cataracts. However, uncontrolled uveitis can also lead to cataracts. So, it is always a balance between good control of the uveitis and the risk of the medications. However, now that we have much better treatments for uveitis in JIA it is more common to be able to use only low doses of steroid drops in combinations with the other therapies.

The uveal tract, which is the middle layer of the eye, is that part of the eye that becomes inflamed in uveitis. As shown in the figure the uveal tract extends from the very back of the eye to the very front, ending as the iris (the colored part of the eye surrounding the pupil). In uveitis associated with juvenile arthritis the inflammation of the uveal tract is usually restricted to just the front part of the eye (involving the iris and ciliary body, as shown on the figure). When the entire uveal tract is involved, from the very back of the eye to the very front, it is referred to as pan uveitis. \

While pan uveitis can occur in children with arthritis it is much less common that the uveitis that is restricted just to the front part of the eye (the iris and ciliary body involvement only, which is referred to as anterior uveitis). In addition to occurring in association with juvenile arthritis and other autoimmune diseases, pan uveitis can occur in association with certain infections, and eye injury or surgery, as examples. The inflammatory process involved with pan uveitis and anterior uveitis seems to be similar but further research is required to better explain why some children have anterior uveitis and others pan uveitis.

The course and outcomes of uveitis, including uveitis associated with juvenile arthritis, are variable; some children will have ongoing lingering disease activity and others can go into long-term control (remission). At the present time we can make decisions about treatments based on experiences from large groups of patients with similar conditions. However, the conclusions we make about the diseases and the treatments from studying the group as a whole do not always precisely apply to individual patients within the group, there is considerable variability in how individual patients will respond to treatment.

Now, with new knowledge and technologies, we are beginning to aim for personalized approaches to therapy so that we can select therapies based on the individual’s genetic, lifestyle and environmental factors. We think this personalized approach will result in more uniform and effective responses to therapy. In general, older data suggests that about 1/3 of patients with uveitis associated with juvenile arthritis will have mild or no active disease long term, 1/3 may continue to have mild to moderate disease, and 1/3 will have substantial long term visual impairment. However, more recently, with earlier diagnosis, more rigorous follow up and monitoring of patients, and dramatically improved treatments, we anticipate the long-term outcomes will greatly improve.

We don’t have enough information to answer this question precisely but it is almost certainly true that with early diagnosis, careful monitoring and use of new medications the possibility of permanent remission increases. I wouldn’t say children can “outgrow” uveitis exactly but with proper treatment the abnormal process that gives rise to the uveitis could be stopped with therapy. We hope permanent remission of uveitis can occur with early treatment and new treatments.

The course and outcomes of uveitis, including uveitis associated with juvenile arthritis, are variable; some children will have ongoing lingering disease activity and others can go into long-term control (remission). Now, with new knowledge and technologies, we are beginning to aim for personalized approaches to therapy so that we can select therapies based on the individual’s genetic, lifestyle and environmental factors. We think this personalized approach will result in more uniform and effective responses to therapy. In general, older data suggests that about 1/3 of patients with uveitis associated with juvenile arthritis will have mild or no active disease long term, 1/3 may continue to have mild to moderate disease, and 1/3 will have substantial long term visual impairment. However, with earlier diagnosis, more rigorous follow up and monitoring of patients, and dramatically improved treatments, we now anticipate that long-term outcomes will greatly improve.

At the present time we can make decisions about treatments based on experiences from large groups of patients with similar conditions. However, the conclusions we make about the diseases and the treatments from studying the group as a whole do not always precisely apply to individual patients within the group; there is considerable variable in how individual patients will respond to treatment. Now, with new knowledge and technologies, we are beginning to aim for personalized approaches to therapy so that we can select therapies based on the individual’s genetic, lifestyle and environmental factors. We think this personalized approach will result in more uniform and effective responses to therapy. With earlier diagnosis, more rigorous follow up and monitoring of patients, and dramatically improved treatments, we anticipate the long-term outcomes of uveitis will greatly improve.

The new treatments that are available to treat uveitis (and arthritis) have transformed care and outcomes. The new treatments are referred to as biologic drugs because they are designed to target the precise molecules that participate in inflammation. Currently, these biologic drugs target molecules in the body that usually participate in inflammation. However, with more research we hope to be able to identify exactly what molecule or molecules participate in inflammation in the individual patient so that the exact correct choice of the biologic drug can be selected for that patient. Also, with more research we hope to be able to know better when the biologic drug should be started and when the medication can be safely stopped without causing the disease to recur. Of course, we are continuing to investigate what factors might be involved in causing uveitis to occur in the first place so that we can consider ways to prevent uveitis from occurring. New biologic treatments, that target an increasing number of proteins that contribute to inflammation, are being developed at a very rapid pace so new drugs are becoming available on a regular basis.

Assessing the microbiome is a complex, laboratory-based process. Doctors cannot effectively assess the microbiome by asking the patient questions or by findings on a physical examination. To effectively assess the intestinal microbiome a stool sample needs to be collected and processed in the laboratory so that the molecular and genetic characteristics of the bacteria in the sample can be determined. To determine which bacteria are in the sample from the intestine the laboratory will determine the genetic characteristics of each of the bacteria. We are also beginning a study that will be investigating the oral microbiome by collecting saliva samples and samples from around the teeth and gums as we suspect that the oral microbiome might have some influence on juvenile arthritis. We don’t know if the oral microbiome might be associated with uveitis but our study should help improve understanding of this possible connection.

This is a fascinating question and one for which there is accumulating but still minimal information. There is some evidence that maternal use of antibiotics either before or during pregnancy or at the time of labor might result in changes in the microbiome of the child born to that mother. There have been no studies done specifically to investigate if maternal antibiotic use during pregnancy might affect the risk of the child developing JIA or uveitis. We are currently doing a research study to investigate how inflammation during pregnancy might influence future disease in the offspring. One facet of this study is to look at antibiotic use during pregnancy and the risk of the offspring having certain diseases later in life. We are also just about to begin a research project to study if the microbiome in the mouth influences the occurrence and course of JIA and if there is any connection with the oral microbiome and uveitis.

Recently, a group of Canadian pediatric rheumatologists, pediatric ophthalmologists and patients and parents have been working together to develop standardized approaches for monitoring and treating children with uveitis associated with JIA . It was felt important to develop standardized approaches because there is some variability in how children with JIA uveitis are managed. In both the Canadian and similar United States guidelines that are being developed in children with JIA and uveitis who are starting treatment other than eye drops for uveitis, using injection of methotrexate is recommended over oral methotrexate.

In general, evidence suggests that injection of methotrexate works better for both arthritis and uveitis. Thus, if the child was on oral methotrexate before the injection and the switch was made to achieve better control of the JIA and/or uveitis, then switching back to oral methotrexate might or might not result in a flare. The decision the doctors might have to consider is not when to switch to back to oral methotrexate but when to try to discontinue methotrexate entirely. Deciding when to stop methotrexate would depend on how severe the uveitis was, how difficult it was to control, and if the child is on other medications. In the guidelines that are being developed, in children with uveitis that is well controlled on a medication such as methotrexate with or without other therapy, it is recommend that there be at least 2 years of well-controlled disease before tapering and then discontinuing the therapy.

So, in a child with at least 2 years of inactive disease one might soon consider beginning a slow taper of current medications rather than switching to oral methotrexate. But again, this depends a lot on the individual patient’s characteristics and treatments now and in the past. Studies are underway to gather evidence that will help guide when medications can be safely stopped without risking flare ups.

Long term effects of uveitis can be minimized by prompt diagnosis, consistent monitoring, and appropriate use of medications. Some of the main effects that can occur and which we try to avoid with therapy include the following:

- Decrease in vision: When there is inflammation in the eye, such as occurs with uveitis, there can be increased amounts of protein and inflammatory cells in the eye that interfere with light passing through the eye. As a result, the ability to see clearly can be reduced.

- Cataracts: A cataract is a painless clouding of the usually crystal clear lens of the eye. The lens sits behind the pupil of the eye as shown in the figure. Cataracts block light, making it difficult to see clearly.

- Synechiae: Synechiae can occur as a result of uveitis. Synechiae are adhesions of the iris so the lens becomes stuck to either the lens below or the cornea in front (the cornea is a clear membrane window that lies in front of the pupil). When such adhesions occur, the iris will not move as freely. Normally the iris will dilate (spread out) so the pupil enlarges when the environment is darker (allowing more light to enter the eye) and in bright light will constrict (come together) so the public gets smaller limiting the amount of light entering the eye. When synechiae are present the movement of the iris is impeded and this can result in difficulty in adapting to light changes in the environment.

- Band Keratophathy: Band keratopathy is a line or band that appears across the center of the cornea. The band forms when calcium deposits collect in this area. Band keratopathy can reduce vision and sometimes causes eye irritation or redness.

- Increased eye pressure (glaucoma): Glaucoma can occur in some children with uveitis because the normal flow of fluids in the eye might be limited because of the inflamed tissues. Steroid medications can sometimes increase the eye pressure.

This is a very interesting and important question. Yes, uveitis can result from injury to the eye such as a blunt force to the eye or a foreign body in the eye. This usually results in iritis, which is inflammation of the colored part of the eye that surrounds the pupil. The iris is also one part of the eye that is typically inflamed in uveitis associated with JIA. There is also information from laboratory experiments suggesting that trauma in a joint can result in changes in certain molecules in the cornea of the eye (a part of the eye which is not primarily involved in uveitis associated with JIA). More research needs to be done to understand how trauma to the eye or in the joint might be associated with chronic uveitis as is seen in association with JIA.

There are seven different types of Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis.. It is uncommon for most forms of JIA to occur in siblings; children who present with the type of JIA referred to as ERA (Enthesitis Related Arthritis ; enthesitis refers to inflammation where ligaments and tendons insert onto bone), which tends to occur in older children and is more common in boy, are more likely than other JIA subtypes be found in siblings. In children with the type of JIA referred to as oligoarticular JIA (children with fewer than 5 joints involved; the word “oligo” comes from the Greek word meaning “few”) are the most likely to have uveitis that is chronic and generally not associated with symptoms such as redness of the eyes or eye pain . Oligoarticular JIA occurs uncommonly in siblings but it can occur. The occurrence of oligoarticular JIA with associated uveitis is even more rare but again it can occur. The type of uveitis associated with ERA tends to be associated with symptoms and intermittent brief courses; this type of arthritis is thought to be somewhat more likely to occur in siblings with the ERA type of JIA but the occurrence is still uncommon. The fact that JIA and JIA with uveitis can occur in siblings, although rarely, suggest the possibility of a genetic influence on the occurrence of the disease or an environmental exposure or, perhaps more likely, an interaction of genes with the environment. More research is required to answer this important question. Because JIA and JIA with uveitis occur rarely in siblings, international research collaboration, such as that which is being led by Canadian pediatric rheumatologists and ophthalmologists, will be important to help answer this question more thoroughly.

At present, we can decide treatments based on experiences from large groups of patients with similar conditions. However, the conclusions we make about the diseases and the treatments from studying the group as a whole do not always precisely apply to individual patients within the group; there is considerable variability in how individual patients will respond to treatment. Now, with new knowledge and technologies, we are beginning to aim for personalized approaches to therapy so that we can select therapies based on the individual’s genetic, lifestyle, and environmental factors. We think this personalized approach will result in more uniform and effective responses to therapy. In general, older data suggests that about 1/3 of patients with uveitis associated with juvenile arthritis will have mild or no active disease long term, 1/3 may continue to have mild to moderate disease, and 1/3 will have substantial long term visual impairment. However, more recently, earlier diagnosis, more rigorous follow-up and monitoring of patients, and dramatically improved treatments, makes us believe that the long term outcomes will significantly improve.

The new treatments that are available to treat uveitis (and arthritis) have transformed care and outcomes. The new treatments are referred to as biologic drugs because they are designed to target the precise molecules that participate in inflammation. At the present time these biologic drugs target molecules in the body that usually participate in inflammation. However, with more research we hope to be able to identify exactly what molecule or molecules participate in inflammation in the individual patient so that the exact correct choice of the biologic drug can be selected for that patient. Also, with more research we hope to be able to know better when the biologic drug should be started and when the medication can be safely stopped without causing the disease to recur. Of course, we are continuing to investigate what factors might be involved in causing uveitis to occur in the first place so that we can consider ways to prevent uveitis from occurring.

Research is crucial to advancing knowledge about the causes, mechanisms, and treatment for uveitis. In all our research now, including our studies relating to uveitis and childhood arthritis, we ensure that parents and patients are represented on our research teams. We feel it is important for patients and parents to contribute their ideas and perspectives as we develop research projects, interpret results, and disseminate our research results to end-users such as health care providers, administrators, and patients and families. For conditions such as uveitis and childhood arthritis, most of the time, we do not know the cause of the disease, we do not fully understand the mechanisms of the disease, we have treatments that are much improved but still not as predictably effective or as safe as we desire, and we have no insight into cure and prevention. However, there has been astonishing progress in gaining new knowledge. Based on that new knowledge, it is likely that uveitis and childhood arthritis occur because of multiple factors, including, as examples, genetics, environment, and lifestyle.

Parents can help by identifying possible factors that they wonder might influence the diseases’ occurrence and courses. We encourage parents to ask questions, share their thoughts, and participate fully in the process of learning more. Parents should not feel hesitant to ask questions and share their thoughts. It is also important for parents and patients to share their thoughts about the therapies they receive in terms of their effectiveness and side effects. As technologies advance, we can now aim to personalize treatment approaches; that is, rather than selecting therapies for groups of children with similar conditions, we are now beginning to individualize treatment choices for individual children based on their unique genetic, environmental, and lifestyle considerations. Parents and the patients themselves will be crucial in helping to make personalized choices for therapy.

In children with the type of juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA; the word “idiopathic” means the cause is unknown) referred to as oligoarticular JIA (children with fewer than five joints involved; the name “oligo” comes from the Greek word meaning “few”), the antinuclear antibody test (ANA) is positive in about 90% of children. This type of arthritis is most common in young children and more common in girls. In this type of arthritis, about 10% of children might have a negative test for ANA. It is unclear if having a negative ANA in these children affects the severity of the uveitis; in the past, there was some suggestion that the course of the uveitis might have been somewhat less favorable in those who are ANA negative because they were not followed with eye examinations as rigorously as those who had a positive ANA. However, there is no substantial evidence that the uveitis course is substantially different in children with and without ANA. Children who present with the type of JIA referred to as ERA (Enthesitis Related Arthritis; enthesitis refers to inflammation where ligaments and tendons insert onto bone), which tends to occur in older children and is more common in boys, are almost always ANA negative. Their uveitis tends to be more episodic and associated with symptoms such as redness and eye pain.

Some children with arthritis and uveitis might eventually go on to develop psoriasis (a skin condition) or inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn’s Disease or Ulcerative Colitis); both of these conditions can be associated with uveitis in some children, and they are more likely than oligoarticular JIA patients to have a negative ANA test (although some might have a positive ANA test). So, while the ANA test is a marker for uveitis associated with a specific JIA class, a positive ANA test is not essential for making the diagnosis of uveitis and, at this time, is not known to predict the outcome of the uveitis.

In our treatment of JIA, we often initially start with NSAID (e.g. naproxen) and may use corticosteroid joint injections for a few large joints. If this allows patients to achieve remission, then typically a disease modifying anti-rheumatic drug (DMARD) such as methotrexate is not required. However, if there is any residual disease activity after NSAID and injections (for example, in small finger or toe joints, or jaw [TMJ]) then a DMARD would be indicated. Also, if the joint injections don’t have a lasting effect, a DMARD may be beneficial. An advantage of using a DMARD is that it can also help to prevent additional joints from becoming affected by arthritis, and prevent joint damage in the long term.

Our Canadian research, looking at over 1,000 children newly diagnosed with JIA, has shown that the most important contributors to probability of uveitis are a positive ANA and being diagnosed at a young age. Uveitis was most commonly seen in children with either oligoarthritis or polyarticular rheumatoid factor negative JIA. We also saw that there was an incidence of new uveitis among these children of 2.8% per year for the 5 years of the study. This means that children with JIA need to continue to be screened for uveitis for at least 5 years after diagnosis.

There are 7 recognized subtypes of JIA, and ‘oligoarticular’ disease refers to children who have 4 or fewer joints affected at diagnosis. Some oligoarticular cases can ‘extend’ after 6 months to involve 5 or more joints while others ‘persist’ as oligoarticular. In terms of treatment, this is tailored to the specific patient situation. NSAIDS (naproxen) and cortisone joint injections are often used initially when few joints are affected. However if this is not sufficient for achieving remission, then a disease modifying anti-rheumatic drug (DMARD) — the most common of which is methotrexate – is typically added. The treatment may be the same, whether a child has either oligoarticular or polyarticular disease.

Involvement of the TMJ joint is very common in JIA and is most often without symptoms like pain or stiffness. Most commonly, a pediatric rheumatologist notices changes in the movement of the TMJ or growth of the jaw bones which prompts an evaluation for TMJ disease with an MRI. TMJ involvement does occur in oligoarthritis but would be more commonly seen in polyarthritis patients. How to best diagnose, treat and monitor TMJ arthritis is an active area of research in pediatric rheumatology. At this time, our approach is to treat the TMJ if it is significantly inflamed with medications including DMARDs (e.g. methotrexate) +/- biologics to attempt to decrease the risk of long-term complications. This could include facial bone growth abnormalities, need for orthodontics, oral surgery, chronic TMJ pain and sleep apnea. We also often seek advice from our dental colleagues regarding the need for a splint or other specific dental care.

There are many causes for disease flares in JIA which may include changes in medications including interruptions or delay. Emotional, social and physical stressors may be important in disease flares. A potential association of puberty and hormonal changes and disease flare has not been evaluated formally in a research study. As such, at this time we do not have evidence that hormonal changes are related to JIA flares. There are many causes for joint pain that are separate from inflammatory joint disease. It is possible that hormonal changes may be associated with joint and muscle aches.

Yes! As a pediatric rheumatology community, we are very hopeful about the effectiveness of our medications and physical rehabilitation as we are successfully able to achieve remission for the majority of our patients. Recent data from research on Canadian children with arthritis has shown that more than 75% of patients will be in remission within 2 years of diagnosis and depending on the subtype this number may be higher. Furthermore, one half of patients are able to stop medications within 5 years of diagnosis. Depending on the subtype, however, some children will have to restart medications within 1-2 years of stopping them because of disease flare. This risk is highest in patients with polyarthritis who have a positive rheumatoid factor; 2/3 of these patients will have to restart medications within the year of stopping. The goal for each patient is to achieve disease remission and thrive in their physical, social and emotional development. For some patients, this will be whilst taking medications long term but for others this may be achieved with medications and maintained after stopping medications. Being able to predict which children will be able to successfully stop medications particularly biologics is an active area of research in our community.

Children with JIA can develop uveitis at any time, even when their arthritis is not active. For some children with JIA, the arthritis inflammation becomes quiet, but they have continued uveitis requiring treatments. Similarly, arthritis can flare up at unpredictable times as well. The inflammation isn’t ‘switching back and forth’- the inflammation of JIA can involve different areas at different times.This is the reason that it is important for children with arthritis to have eye examinations as recommended by the pediatric rheumatologist and ophthalmologist even when a child appears to be well! In patients with both uveitis and arthritis we always try to select treatments that are effective for both areas of inflammation.

Prednisone (corticosteroid) is a very effective and quick-acting medication that shuts down inflammation in a variety of conditions including arthritis, lupus and vasculitis. It is very beneficial for getting one’s disease under control and helping your child feel better quickly. However, it is associated with many side effects with long-term use. As such, our approach is to use prednisone for as short a time and at as low a cumulative dose as possible. We often will introduce a ‘maintenance’ treatment at the same as, or shortly after, starting prednisone that will eventually take over controlling the disease once prednisone has been weaned down. We often use the metaphor of ‘putting out a fire’ – prednisone is the big hose of water to put it out quickly, while the maintenance treatment helps to prevent the fire from recurring. Typically these treatments have less side effects than prednisone. Of note, it is very important that prednisone is not stopped abruptly, as your child’s body is not used to producing its own cortisol which can lead to problems.

There are many causes of joint pain in children and adolescents. Arthritis is one we are always on the lookout for. However, there are many other factors that may cause joint pain in children with arthritis and those without. One common example is hypermobility – when the joints are very flexible – which can be associated with some joint discomfort. Other potential causes of joint pain include patellofemoral syndrome (i.e. ‘loose’ knee caps), flat feet, ligament or tendon problems, or overuse. In children with JIA, there may also be some degree of joint damage that could result in persistent pain. There is also some evidence that children and adolescents with JIA can be sensitized to feel more pain because of the prior inflammation. Overall, it is important to bring up pain and other joint symptoms to your rheumatology team so that they can be evaluated and addressed appropriately.

When a child or teen with JIA has active disease, or a flare of disease, in joints in the legs (hips, knees, ankles, feet), it can affect their ability to walk. This is usually due to pain in the affected joints. At the time of JIA diagnosis, approximately 30-40% of children may have some trouble with walking, running, or ability to keep up with their usual activities. Our Canadian research data shows that the majority of children newly diagnosed with JIA can reach inactive disease by 6 months after diagnosis while on treatment- this means their arthritis is controlled on medication. Children with JIA whose disease is controlled on medication are able to walk, run, play sports and keep up with their healthy peers. Overall, in 2020, most pediatric rheumatology teams would see few children with JIA who are needing to use equipment such as crutches or wheelchairs for more than a brief time period.

An excellent book is Your Child with Arthritis: A Family Guide for Caregiving by Dr. Lori B. Tucker, Bethany A. DeNardo, Dr. Judith A. Stebulis, and Dr. Jane G. Schaller.

Children with arthritis are not just kids with an adult disease. Although the drugs and therapies used to treat children are similar, the intensity of treatment and the frequency of follow-ups need to be much greater.

Unlike for adults with arthritis for example, physical growth may be stunted, children may grow one leg longer than the other, or one hand or foot may be smaller. Some children with arthritis can also have associated eye inflammation that can lead to blindness. These changes may be irreversible if there is a delay, or poor follow-up, in treatment. The impact of any chronic illness on psychological development, especially during adolescence, should not be underestimated as it can have lifelong recreational, educational, and career implications.

The best outcome for children with any rheumatic disease will be achieved by the involvement of a multidisciplinary team of health professionals such as those at BC Children’s Hospital. In this setting, children will have access to pediatric rheumatologists; specialized nurses, occupational and physical therapists, and social workers whose jobs are dedicated to treatment of children with rheumatic diseases. Other childhood and adolescent medical specialists are also available.

This is very difficult to predict at the outset, and to some extent, it depends on the type of JIA. In a small number of children, the disease may last as little as several months to a year and disappear forever. Most children, however, have an up-and–down course with “flares” and “remissions” for many years with about half of them continuing to have problems into adulthood. While there is no cure for juvenile arthritis, current available therapy often prevents the long-term damage and disability that may be left by arthritis even after it has gone.

Arthritis is diagnosed by examination of the child by a doctor who has specialized training (or experience) in childhood rheumatic diseases. Preliminary evaluation should be by the family doctor or pediatrician, but the final diagnosis is ideally made by a pediatric rheumatologist. There are no blood tests or x-rays to confirm a diagnosis but these tests may be useful to determine the type of arthritis, to assess the severity, or to identify complications.

A child with arthritis may have an obviously swollen joint, or he/she is stiff when waking up and might walk with a limp, or may have trouble using an arm or leg. Children do not always complain of pain because they may adjust the way they do things so that it hurts less, or they may simply ask to be carried more often. With some of the more serious types of JIA, children may also have a fever, a rash, or feel very weak and fatigued.

JIA is not the same as rheumatoid arthritis! In the United States, some forms of childhood arthritis are still somewhat inaccurately referred to as juvenile rheumatoid arthritis or JRA even though the pattern of arthritis and the short-term and long-term effects of most types of juvenile arthritis are completely different from rheumatoid arthritis in adults. Less than 5% of children with JIA have a subtype of arthritis that resembles rheumatoid arthritis.

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis is the newest and preferred terminology to describe chronic arthritis in children. Idiopathic means unknown cause or spontaneous origin. The disease is also sometimes referred to as juvenile arthritis (JA) or juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (JRA). Children under 17 years of age who develop inflammation in a joint (usually with swelling and/or pain and/or morning stiffness) that lasts longer than six weeks usually have JIA. There are seven different types of JIA, and the pattern of arthritis and the short-term and long-term effects of each type are different. We do not know the cause of any of the types of JIA. If the arthritis is associated with another disease such as lupus, dermatomyositis, inflammatory bowel disease or even leukemia, the arthritis is not known as JIA.

About 1 in 1,000 children have juvenile arthritis. This includes children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) and those with other rheumatic or connective tissue diseases. If children with orthopedic and congenital problems that may develop into osteoarthritis in adulthood are included, then an average of one to five children in every elementary school have a chronic rheumatic disease.

Children can get chronic arthritis – called juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA), previously known as juvenile rheumatoid arthritis – as well as other rheumatic diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus (known as lupus or SLE), juvenile dermatomyositis, or vasculitis.

Gym Class and Sports Information

For many children with JIA or other rheumatic diseases, physical challenges at school can be huge barriers, particularly when it comes to gym class. In a recent study, researchers found that 38% of kids with JIA were unable to participate in gym with their peers. Paired with misunderstanding and lack of knowledge on the part of teachers and classmates, this can results in social concerns and anxiety about being unable to complete school related activities, being treated differently and looking like they’re not trying.

To dispel some of this misunderstanding, Dr. Tommy Gerschman, Pediatric Rheumatologist specializing in pediatric sports medicine, exercise and health, answers six essential questions about participating in sports and gym class with JIA. Looking for more information? Join Dr. Gerschman and physiotherapist, Julia Brooks, at the Physical Activity Webinar on January 30th, 2021.

Yes! Physical activity is key to healthy development of children, including those with JIA. Current Canadian guidelines recommend that children aged 5-17 years of age participate in at least 60 minutes of moderate-vigorous physical activity per day. For at least three of these days the activities should promote muscle and bone strength. PE classes at school can contribute to these goals and also teach children important skills such as throwing, running, catching, jumping, and others. Learning to have fun with participation in either individual or team sports is also an important benefit of PE classes. Children with JIA have the same benefits and need for physical activity as other children. In fact, children with JIA might benefit even more from the overall strengthening of muscles and bones that comes from physical activity. Children with JIA can safely participate in sports without fear of exacerbating their disease, but there are some accommodations that should be considered in certain circumstances.

Children with JIA have, from time to time, a number of valid reasons to be excused from participation in PE or gym class. Children with JIA can have increased aches and pains in muscles or joints that make participation in certain types of physical activity (e.g. running, jumping) difficult. Other times, stiffness or restriction of range of a joint might also limit certain types of activities for a child. These symptoms can come and go at various times throughout the course of their chronic disease.

Furthermore, during a new or worsening flare of arthritis, when the joint is very swollen and tender, it is often a good idea to back off of some of the physical activities, including PE classes and other sports. In addition to increased pain, when a joint flare is occurring, the muscles around the joint are often not working as effectively and could pre-dispose a child to other sports injuries. More gentle activities, such as swimming or walking, can still be done quite safely.

Schools are able to accommodate for a child with JIA to allow them to participate in PE classes. The teacher should be made aware that the child may need to sit out of some or all activities from time to time when there is a flare of arthritis or symptoms are worse. At other times, the child will be able to participate fully without any restrictions. Children are usually quite good at being able to self-direct such participation. Other accommodations might include alternative activities such as walking instead of running, learning a skill rather than participation in a full game, or participating in components of the activity. During a flare or increased symptoms, a child might also benefit from taking frequent breaks throughout the class. It is important to encourage participation when appropriate and also support the child in building confidence in physical literacy skills.

Children with JIA can participate in sports at all levels of play. Most children with JIA are able to participate in any sport, although accommodations are sometimes needed as described above. Sports provide much needed physical activity and opportunities for socializing and goal-setting. Children with JIA have gone on to compete in international competitions at the most elite levels, play professional sports, and be professional dancers.

Children who have had arthritis affecting their neck should be screened for instability in that area before participation in any contact sports. Children should be reminded to wear protective eye equipment as per the general population. For children who have had uveitis, there might be an increased risk of eye injury in some sports. Children with a history of arthritis in the jaw (TMJ) are advised to wear properly fitted mouth guards for certain sports (e.g. contact) when these precautions are already recommended for the general population.

Most children with JIA are able to continue to play sports without any significant problems. It is important to remember that not all joint or muscle pain is due to arthritis. The above recommendations for accommodation for PE classes can also be applied to sports participation. Many children want to fit in with their team and peers by not sharing their diagnosis but it is important to ensure at least the coaching staff is aware that a child has JIA. Similarly, coaches should be informed that, when well, most children with JIA will be able to participate, without restrictions, as well as other players.

Just like children returning from a sports injury, children who are returning to sport after a flare of arthritis should do so in a gradual manner. As with other children participating in sports, it is important to remember to have at least one day per week off their sports to allow for rest and recovery. Attention should also be considered for a well-balanced diet and adequate sleep.

This is one of challenges for children with JIA who play sports. It is a common question that your pediatric rheumatologist is asked and they can review individual circumstances. In general, JIA pain due to an active joint will be sore every day, regardless of activity, and it may be more significant in the mornings with associated stiffness. Any time there is a new pain associated with a sport it is recommended to take a moment to see if that pain persists or goes away. For any pain that is consistently coming up or lingers for a period of time after the activity, it is worth to review with your doctor and/or physiotherapist. Although there is some pain that is ok to “push through”, most of the time we have to learn how to listen to our body, adapt our activities accordingly, and get some help to figure out what’s going on.

This is a great question to ask your pediatric rheumatologist who will be able to tell you if your child is in remission. Some physical activity, in the form of sports, may still be possible depending on which joints are involved and how active the arthritis is. At this young age the risks of injury are relatively low overall. The key is to move and have fun – and all children with JIA should definitely be doing that!

If you are in a flare it is a good time to take it a bit easier with activity. Doing light activity is ok but you may have to back off of the more intense activities. Pain can help remind you to take a break but not all kids experience pain as part of their arthritis or during activity. I remind families to look for signs that kids have done too much by noticing increased pain during or after the activity or increased pain or stiffness in the joints the next day. If these things happen it is important to think about what happened the day prior and try to do a bit less the next time.

There is an increased risk of injury for a few reasons. Inflammation can inhibit muscle firing making it harder for the muscles to stabilize and protect the joints. Inflammation over time can weaken the ligaments and tendons making them more susceptible to injury. Pain can make us compensate with other movements and therefore put us in a position that may make us more susceptible to injuries. During flares we usually encourage kids to be more careful with high impact/ contact sports.

I would find ways to make it more fun for them such as making it into a type of game (if possible). Another way would be to reward them every time they do them.

I did lots of different sports including competitive swimming and recreational soccer, gymnastics, dance, track and field, and hockey.

Many kids with arthritis actually don’t experience pain. If their arthritis is in remission then no need to limit. If they have mildly active disease then I usually don’t limit them too much. If they have big swollen joints then I try to limit heavy, pounding exercises such as running, jumping repetitively or from a height, trampoline, moguls etc. even if they don’t have pain. Some things to watch for can be the quality of the child’s movement. Even if they don’t verbally complain of pain you may see them alter how they are performing the movement if you watch closely (do they start to put more weight or use one limb more than the other). Another thing to look for is if they seem to be in pain later (they have done too much) or if they look stiff or painful in the joints the next morning. If any of these things are happening it is good to encourage a break in the activity. If you don’t notice anything until the next day or that night then reflect on what they did (ex. 2 hours of skating) and the next time plan to half that (1 hour of skating) and see how they do. It often is a bit of trial and error!

This one is hard and is a common problem. First off see if you can sit down and find anything your child might be interested in trying, sometimes if they get to pick activities they are more motivated. It does not need to be a sport. Second, as the parent, it is important to set an example of activity and an expectation of what that should look like. I try to be active every day and through years of conditioning the kids know they have to incorporate it into their day as well. If they haven’t done anything that day then they know I will be at least making them go outside for a bit! Third, take away screens. This is probably the biggest thing I run into. Kids on screens for multiple hours a day. Set a rule or limit that works for your house. For example- no screens until activity is done (this may be as simple as a walk). Or no longer than 30 (or 60 or whatever you choose) minutes on screens until they are required to take an activity break. Many people, including kids, are not naturally drawn to activity. This often gets harder as they hit their teenage years. At this point it is about activity for health (just as we brush our teeth so they don’t fall out of our head) and may just need to be built into the day as a walk or bike ride or a skate for example. It could also just be a change in active transportation such as walking to school instead of a drive or the bus. COVID-19 has exacerbated this problem quite a bit but it does give us the opportunity to be outside and try new things.

Now the hard part- your kid is possibly going to be mad and frustrated. Change is hard. Don’t give up. It can take several months of the new suggestions to be developed into a habit. Often as parents it can be easier to just let them do what they want so you can get a break (been there!!!). It can be tiring at first but a little extra effort in the short term can reap long term benefits. Finally, start small and set up a plan. Going from 0-60 is not easy but finding 10 minutes a day is much more manageable. Try to be consistent as a family getting in 10 minutes a day for 2 weeks and then try to increase in 5 minute intervals every 2 weeks. This can also be broken up into 10 minute chunks (i.e. not all 60 minutes needs to happen at the same time). Overall consistency is the key. There are going to be days that just don’t happen but if that arises just get back on track as soon as possible!

This blog post was contributed by Dr. Tommy Gerschman, MD, FRCPC, MSc (Sports Medicine, Exercise, and Health), Pediatric Rheumatologist with Special Interest in Pediatric Sport and Exercise Medicine, North Vancouver, BC.